search

date/time

Thu, 6:00AM

overcast clouds

3.7°C

ENE 14mph

overcast clouds

3.7°C

ENE 14mph

| Sunrise | 7:23AM |

| Sunset | 5:26PM |  |

Jeremy Williams-Chalmers

Arts Correspondent

@jeremydwilliams

P.ublished 19th February 2026

arts

Interview

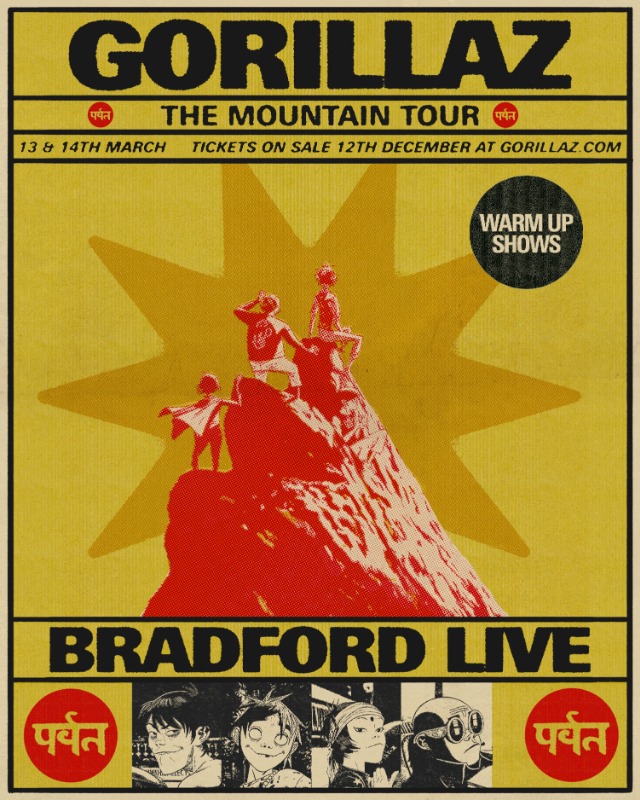

Gorillaz Album: From Belgrade To The Ganges - How Grief Built A Mountain

What could have been a reason to never return to India again took on a completely different meaning. Albarn spent five or six weeks in Jaipur, moving daily between hospital corridors and the teeming streets of the Pink City. Colour, sound, and discovery coexisted with grief and uncertainty. “We need to go to India and do something,” he told Hewlett when he returned. The idea was simple at first: travel, absorb, and collaborate with Indian musicians. The theme would reveal itself later.

It did—brutally. After their first trip together in May 2024, both men lost their fathers within ten days of each other. They had been unwell, but the proximity of the losses felt seismic. Suddenly the album’s emotional core emerged: life, death, passage, and return. India was no longer just a location; it was a lens.

Albarn carried some of his father’s ashes to the Ganges River—not as a grand gesture of belief, but as a personal acknowledgement of a lifelong connection. Raised in a part of London steeped in South Asian culture, he grew up listening to Ravi Shankar and traditional ragas long before he discovered The Beatles. India, spiritually and musically, had been in the background of his life since childhood. Now it was foregrounded by loss.

The duo travelled relentlessly: Mumbai, New Delhi, Varanasi, Rishikesh, back to Jaipur and beyond. It was May—ferociously hot, noisy, and overwhelming. “You have to leave your Western version behind,” Hewlett says. “Melt into it.” India demanded surrender before it offered insight.

A second key session took place on a rooftop in Jaipur’s old city, where a 40-piece wedding band assembled in suffocating heat. Monkeys skittered across power lines overhead; a leaking oil tanker scented the air with petrol; an electricity pylon sparked ominously nearby. In a tiny room approaching 40 degrees Celsius, Albarn attempted to teach dozens of horn players a new composition while chaos reigned outside. It was absurd, dangerous, and ecstatic. It was Gorillaz.

India, however, is only one coordinate in the album’s emotional map. The band’s recent history also passes through Damascus and Casablanca—cities Albarn describes as bearing political scars and intense energies. Belgrade, too, looms large: a place of creative vitality and geopolitical tension. The record began there, just before Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, in a moment thick with foreboding. Albarn now sees that darkness threaded through the album’s more overtly spiritual imagery.

The mountain, then, is both literal and metaphorical. Hewlett describes it as a triangle: broad and lush at the base, narrowing as it ascends. Many paths at the beginning; few at the summit. Beyond the peak lies the “crystal lake” or “moon cave”—a place of transformation or reincarnation. The album opens expansively and gradually contracts, reprising its central theme at the end in The Sad God, a track in which a disappointed deity laments humanity’s choices. “I gave you atoms,” Albarn sings. “You built a bomb.” Behind the line, the faint echo of a falling cartoon coyote collapses tragedy into satire.

That interplay—earnest and absurd, sacred and profane—has always defined 2-D, Murdoc Niccals, Noodle and Russel Hobbs. Gorillaz’ stories are “slightly autobiographical", Hewlett admits: the characters articulate the creators’ experiences through distortion and exaggeration. This time, however, the balance shifts. The sarcasm remains, but it is tempered by reverence—for India, for grief, for continuity.

One centrepiece image—a sprawling centrefold—brings every contributor together in an Indian streetscape. It evolved as the tracklist evolved; as new musicians were added, Hewlett scrambled to find them space. The image is both documentary and impossible: a photo shoot that could never happen, realised because Gorillaz is a cartoon.

Musically, the guest list continues the band’s tradition of cross-cultural openness. Syrian wedding-pop phenomenon Omar Souleyman appears, expanding the record’s geography still further. The result is less a genre exercise than a porous collage—folk fragments, choral swells, electronic textures and brass eruptions refracted through Albarn’s melodic sensibility.

Significantly, the band has resisted the machinery of contemporary promotion. There is no elaborate social media narrative, no breadcrumb trail of algorithm-friendly content. Instead, the album arrives with a substantial art book and an eight-minute hand-drawn animated film created with The Line. Inspired in part by the craftsmanship of The Jungle Book, Hewlett insisted on painted backgrounds and traditional cel-style animation—no AI, no shortcuts. It is slower, more laborious, and truer to the band’s origins.

That return to first principles mirrors the album’s thematic arc. Gorillaz began as an experiment in the marriage of music and moving image; The Mountain reasserts that union. It also reaffirms the creative bond at its core. Albarn and Hewlett have known each other for over three decades. Like any long partnership, theirs has weathered distance and disagreement. But in India—and in grief—they found renewed gratitude for each other’s company.

Is there a definitive narrative? Not exactly. The album invites interpretation rather than dictating it. The mountain is a state of mind. The journey is internal as much as external. Each listener ascends differently.

What is clear is that The Mountain feels like an episode—another chapter in an ongoing, intergenerational project that can regenerate through new imaginations. The animated characters travel on our behalf, returning with stories from beyond the summit. And somewhere, perhaps, it is still 28 November in Belgrade—the moment fate tilted, and a new path began.

Also by Jeremy Williams-Chalmers...

Bluey Live: Puppets, Pandemonium And Pure Joy For The Whole PackCharacter-Led: Nathan Carter On Papal Performances, Robbie Williams' Hitmaker And Why Country Fans Are The Most LoyalTrousdale, O2 Institute 3, BirminghamAlbums: If You Go There, I Hope You Find It, The Paper KitesAlbums: Mika Hyperlove