search

date/time

| Lancashire Times A Voice of the Free Press |

Paul Spalding-Mulcock

Features Writer

@MulcockPaul

8:09 PM 21st October 2021

arts

‘Writer, Maverick, Iconoclast, Visionary’: The Young H.G Wells, Changing The World By Claire Tomalin

For a literary biography to be truly scintillating, engrossing and valuable we must have an undeniably complex and significant individual as our subject, and a supremely competent biographer. The Young H.G. Wells, Changing The World by Claire Tomalin not only richly satisfies the criteria of first class biography, it transcends these tacit stipulations to become an utterly absorbing, entertaining and near faultless delight.

Taking our subject first, H.G. Wells assuredly qualifies as a significant and profoundly interesting subject. Putative father of the science fiction genre, futurist, iconoclast and social reformer, Wells occupies an exalted, if somewhat variegated place in our literary canon. His scientific romances suffused with minatory warnings, floridly imagined dystopian realms and dazzlingly prophetic insights, still remain both venerated and unsurpassed.

Whilst his later work descended into didactic drivel at worst, or irrelevant megillahs devoid of panache or literary legerdemain, the novels written before his fortieth birthday remain disturbing, exquisitely quixotic gems. Exploring the fons et origo of such a proudly influential body of work is every bit as exciting as reading the novels themselves.

We have gained an insight into the deliciously unconventional mind and chequered character responsible for these astonishing stories from the man himself, by dint of Volumes I and II of his Experiment In Autobiography, and his autobiographical memoir, H.G Wells In Love. J. D. Beresford’s excellent collection of essays have shed invaluable light on our eccentric genius, as have a number of scholarly and not so scholarly biographies. Few have managed to balance informed objectivity with story-telling aplomb until now.

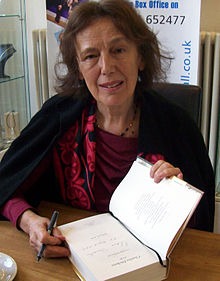

In this case, our biographer is both widely esteemed and prodigiously talented. Tomalin was the literary editor of the New Statesman, then The Sunday Times before devoting herself to biography. Her first book, The Life and Times of Mary Wollstonecraft won the Whitbread First Book Award. Her subsequent works include Jane Austen: A Life and The Invisible Woman, a definitive account of Dickens’ relationship with actress Ellen Ternan, and all have received deserved acclaim.

Samuel Pepys: The Unqualified Self and Charles Dickens: A Life have solidified her place as one of our most gifted biographers, with no less than Hilary Mantel declaring her to be, ‘The finest of biographers’. So, we have a wonderful subject for our investigation, and an undeniably accomplished biographer to act as our guide…little wonder the book is a lambently modulated, rigorously researched delight !

The ace in Tomalin’s pack is to have concentrated her efforts upon the first forty years of Well’s life. In doing so, she has judiciously avoided giving us the orange peel as well as the orange. George Orwell himself concluded that Well’s first four decades produced work influencing an entire epoch and the minds of those navigating its tumultuous waters.

Claire Tomalin in 2013

Tomalin describes Wells’ impoverished childhood, strained relationship with his working class parents, both doomed to quotidian banality and personal failure. We witness Wells attempting to escape life as a draper’s assistant, whilst gorging himself upon books supplied by his feckless father, or purloined from the library in the grand stately home of his mother’s employer.

Tomalin traces Wells’ resolutely autodidactic endeavours to expand his learning, survive two decades of serious ill-health, before moving onto the salacious, amoral details of both his marriages and the colourfully priapic escapades libidinously staining them. We see Wells turn to both writing and Socialism, his uncorralled mind devouring knowledge in order to transform it into literary gold, his novels the channel by which he hoped to change his age, and its values.

Cleverly, Tomalin is sparing with her paint. A skilled biographer must curate their offering with sublime care, omitting that which occludes the essence of their subject, whilst including that which illumes it. Consequently, Tomalin focusses upon the seminal themes running through the life of her subject as though following only the brightest and most significant threads forming the fabric of H.G. Wells himself.

We have an in-depth examination of Wells’ sexuality, or more pointedly his lust for the ‘flame meeting flame’. This primal drive caused the opprobrium and intellectual scorn that brutally undermined both his influence and his social standing. His inextinguishable passion for Socialism and his volatile relationship with the Fabian Society are given careful attention, both ineluctable forces shaping his eccentric mind and blisteringly avant-garde, indeed shocking, work.

Wells was an intuitive intellectual, his mind liberated from the restrictive ideological and political paradigms of his day because he was and remained an outsider, albeit a famous one. Out manoeuvred by Bernard Shaw’s sophistry and executive power, Tomalin dextrously demonstrates how anti-Shaw factions within the Fabian movement sought to rejuvenate its ideology by dint of Wells’ energies.

These internecine battles only succeeded in shoving him ever further into the long grass of grandiose utopian musing and cast him thereafter as a once great prophetic voice, no longer able to prophesy. Hardly surprising that Wells obdurately tried to reclaim his place and influence with tenacity, despite having little more to say and few genuinely influential ears to bend.

We also see, if not forensic, then attentive focus given to the personal friendships adduced to have been those most influential in moulding his psyche and mutable self-perception. By exploring these synergic factors and sensitively following the catena of events catalysed by them, Tomalin gives us an impressionistic, delicately nuanced portrait of real value because she acquaints us with the unadulterated holistic essence of the man, not his assumptively etched effigy.

Also by Paul Spalding-Mulcock...

Word Of The Week : CorpusThe Gallery, Slaithwaite: ‘Ten’ - A Birthday ExhibitionWord Of The Week : SibilantWord Of The Week : PropinquityWord Of The Week : IdiosyncrasyOne device artfully employed by Tomalin is to provoke a question in the reader’s ever curious mind and then proceed to immediately answer it. Supercilious biographers disgorge their knowledge without concern for the reader’s desires, all too often as an egregious, self-aggrandising display of their recondite wares. Gifted biographers take their readers on a journey, the facts acting as flagstones on the path…noted, but not at the expense of the surrounding views. For me, Tomalin falls into the camp of gifted biographer, sans ego and the almost unseen servant of her respected reader.

Another factor lending any biography gravitas, is the degree of scholastic rigour employed in its making. One has only to investigate the index, chapter reference notes and comprehensive bibliography to have confidence in the veracity of Tomalin’s account. A reader senses when an author has mined vast tracts of knowledge, but left most of it off the page…Tomalin’s subject matter expertise is never in doubt, and consequently we follow her lead without doubt or hesitation.

If I were pressed to find fault, Tomalin does venture beyond the prescribed timeframe she set out to explore. The book concertinas aspects of Wells’ later life into the final chapters if not incongruently, then with rather too much haste. In her defence, our biographer became fascinated by her subject and could not resist the allure of following him a little further into the wilderness. That said, these brief chapters do lend the book a little beneficial breadth, and this serves to make it an appealing read for the reader wishing to know Wells in totality, without wading through copious additional material.

Neatly summarised by Beatrice Webb in her diary note of the 19th April, 1904, Wells was, ‘a romancer spoilt by romancing’. Tomalin has given us a picture of Wells capturing the salient facts, but more importantly, helping us to understand both the man and his work. It’s a biography both pellucid and utterly riveting, and one I will happily add to the bookcase groaning with the works penned by an author who electrified my young mind, and continues to galvanise it now…despite its antiquity!

The Young H.G. Wells, Changing the World is published by Viking